Saudi King Salman Shuffles the Deck

By Stephen Schwartz

On Wednesday, April 29, King Salman Bin Abd Al-Aziz of Saudi Arabia announced a set of changes to his cabinet. Salman, 79, assumed the throne after the death of his half-brother, King Abdullah Bin Abd Al-Aziz, in January.

Abdullah, who was 90 or 91, earned a reputation as a reformer of the desert kingdom's harsh social and theological system, founded on the ultra-radical doctrines of the Wahhabi sect of Islam. Abdullah built large coeducational universities, relaxed limits on media, appointed 30 women to the unelected and previously all-male 150-member Shura Council, a national consultative body, and ordered that women be granted the right to run as candidates and vote in municipal elections scheduled for this year.

When he took over three months ago, Salman appeared as a probable upholder of Abdullah's legacy, if only for the sake of a stable transition. He named Prince Muqrin, now 69 and another half-brother, as crown prince, the official successor. Prince Muhammad Bin Nayef, Salman's 55-year-old nephew and the son of Salman's full brother, the late crown prince Nayef Bin Abd Al-Aziz, became deputy crown prince, second in line of succession. Muhammad Bin Nayef also retained the office of interior minister, to which he had risen after a career with responsibility for anti-terrorism duties that began in 1999. The upshot of the cabinet changes yesterday is that Prince Muqrin has been pushed aside, and the younger Nayef is now crown prince, and next in line for the throne.

The Sudairi faction of the royal family has regained control over the summit of the Saudi state.

|

Prince Nayef was feared deeply by Saudis and by Muslims around the world as the epitome of Wahhabi puritanism, and his son, Muhammad, was seen as little better. Nayef was notorious for portraying the al Qaeda assault of September 11, 2001, as the purported work of "Zionists."

Princess Maha Bint Muhammad Bin Ahmad Al-Sudairi, in Vanity Fair, April 2015

|

Yet a startling reportage in the April 2015 issue of Vanity Fair revealed another aspect of Prince Nayef's character. Maha Bint Muhammad Bin Ahmad Al-Sudairi, the favorite wife of Prince Nayef until their divorce in 2012, just before his death, was depicted in the magazine with her face covered—not with a black niqab, the Saudi veil hiding everything but the eyes, but with an elegant Renaissance costume mask that concealed little of her features. She had, it was reported, racked up millions of dollars of unpaid bills at hotels, couture houses, and discount clothing stores in Paris.

Princess Maha engaged in such shenanigans while ordinary Saudi women were (and remain) deprived of the right to leave their homes without putting on the all-covering black garment known as the abaya. They cannot drive vehicles on the roads, or meet unrelated members of the opposite sex in public, or be employed unless they are accompanied by a male guardian. Other restrictions weigh upon them. Given that Nayef apparently indulged his wife's non-Wahhabi behavior and spending sprees when outside the kingdom for so long, it may be unwise to speculate, at this early moment, on the future conduct in office of his son, Muhammad Bin Nayef.

King Salman, and three more who are deprived of succession rights, now comprise the last of the direct Sudairi sons of Ibn Saud. With the latest shifts in position, Muhammad Bin Nayef will become crown prince, a step up, pushing the non-Sudairi Prince Muqrin out of the line of succession. Muhammad Bin Nayef will still keep his post as minister of the interior, according to the official website of the Saudi Embassy in Washington. King Salman's son Muhammad Bin Salman, only 30, will be deputy crown prince, or second in line for royal authority, while similarly preserving his influence as defense minister, a job he has occupied since earlier this year.

The transfer of powers to a younger generation of princes signals a decline in the dominance of Saudi Arabia by the aging sons of its founder.

|

That seems unlikely. Reconsolidation of the Sudairis at the apex of the Saudi state surely reflects anxiety over the position of the country between the fires of the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq, and the Iran-backed Houthi uprising in Yemen. Salman is concerned especially about the horror—and, to Muslim ultra-radicals acting supposedly to "defend Sunnis," the appeal—of the metastasized Wahhabism of the Islamic State.

Reforms may slow down as attention is diverted to defense of Saudi Arabia from extremism; or they may accelerate as the rulers seek to unite the people behind them. The transfer of powers to members of the younger generation of princes, such as Muhammad Bin Nayef and Muhammad Bin Salman, signals a decline in the dominance of Saudi Arabia by a gerontocracy. The Jidda-based Arab News praised Salman's latest appointments as an empowerment of the next generation.

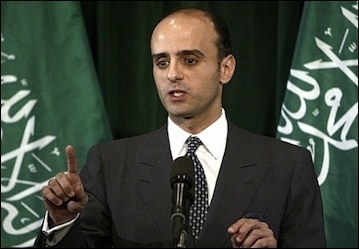

Adel Al-Jubeir, 53, is the first Saudi foreign minister who is not a member of the royal family.

|

In the set of cabinet changes, one was genuinely extraordinary: Adel Al-Jubeir, the 53-year-old Saudi spokesman who was criticized for his opaque attitude toward the involvement of Saudis in 9/11 immediately after the terrorist assault took place, has become foreign minister, after heading the Saudi Embassy in Washington since 2007.

Al-Jubeir was preceded in the foreign ministry by Prince Saud Al-Faisal, now 75, who has run the ministry since 1975. Saud Al-Faisal will continue to serve in the cabinet, as an adviser to Salman. Al-Jubeir was markedly more sophisticated in his dealings with the United States than the earlier occupant of the Washington embassy, Prince Bandar Bin Sultan, who was known for his crude interference in American politics during his tenure from 1983 to 2005.

King Abdullah summoned Bandar home, and after a brief resurfacing during the earlier period of the Syrian crisis, Bandar was banished from Saudi ruling circles. His exclusion seems to have been affirmed by Salman. Bandar's father, crown prince Sultan Bin Abd Al-Aziz, who died in 2011 at 82 or 83, was among the Sudairi Seven, and Bandar's removal from the scene would appear indicate that pragmatism, rather than clan self-interest, drives the decisions of Salman.

More significantly, Al-Jubeir is the first Saudi foreign minister who is not a member of the royal family. With the foreign ministry suddenly out of the hands of the royals, Saudi Arabia may have taken a step toward its normalization as a state. Given the turmoil with which it is surrounded, and from which it has been spared internally, transfers of power to civil, rather than hereditary, leaders cannot come too soon. Such a transformation would include the expansion of women's rights and those promised 2015 local elections, with real competition, clean voting, and legislative power.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home