Fears of Shia muscle in Iraq's Sunni heartland

By Jim Muir

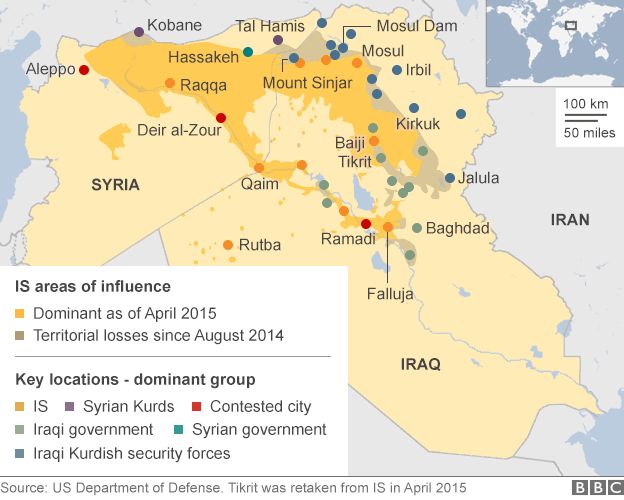

If it has not been already, the die will be cast for Iraq's future - both medium and far - by what happens in the next days and weeks in western Anbar province, following the capture of its capital Ramadi by Islamic State.

Its fall was a massive blow to the Iraqi army, to Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi and to the US, who had encouraged his policy of relying on the official armed forces and police and ruling out a role for Iranian-backed Shia militias.Their action so deep inside the Sunni heartlands would raise fears of sectarian repercussions.

But the collapse at Ramadi left Mr Abadi with no choice but to give the green light for the Shia militias of the Popular Mobilisation (al-Hashd al-Shaabi) to go in.

They have the approval - again late in the day - of the largely Sunni provincial council, which had also been wary of allowing the Shia forces to play a role.

'Lesser evil'

But Sunni opinion is deeply split and troubled. Many are greatly concerned about the penetration into their areas of the Shia militias - organised and directed by Iran and its ubiquitous supremo in Iraq, General Qasem Soleimani.

Little has been done to meet those Sunni grievances, despite agreement on issues like setting up a National Guard, which would devolve security responsibilities to local groups, and calling off the purges of regime loyalists after the overthrow of Saddam Hussein in 2003.

The prime minister, who comes from the same Shia religious party as Mr Maliki, is seen as well-meaning but unable to stand up to the Shia militias and their Iranian backers.

"The process of empowering the Sunnis has not even begun," said one well-placed Sunni politician.

"The Sunnis are getting to the point where they think that Islamic State is a lesser evil than the Shia militias."

Yet the Shia militias are pressing deeper into Anbar province. Much will depend on how they behave if they are victorious, and who will fill the security vacuum if IS is pushed out.

The spokesman for the Popular Mobilisation, Yousif al-Kilabi, stressed the militias would be operating under official auspices.

But such talk in the past has been largely fictitious, and the precedents are not encouraging.

The Shia militias played a key role in "liberating" another mainly Sunni provincial capital, Tikrit, from IS militants at the end of March.

Admittedly the excesses could have been worse. As Mr Abadi put it, "only" about 60 Sunni properties were burnt or destroyed in revenge (others put the figure at up to 200), and not many Sunnis were murdered.

But while the area is now officially under the control of the army and police, sources there say it is the Popular Mobilisation that is really in charge, and none of the thousands of Sunni inhabitants who fled have been allowed back.

The area of Jurf al-Sakhar, south-south-west of Baghdad, has been similarly cleared of its Sunni population to create a security buffer between Anbar and the Shia holy cities of Najaf and Karbala to the south.

Local sources say 3,000 Sunni homes have been razed there and 7,000 families displaced and not allowed to return.

"You'd have to kill half the Sunnis of Iraq to secure the Shia areas," said one local leader, arguing that the Sunni regions should be given responsibility for their own security and for weeding out IS sympathisers, a task they say only they can accomplish.

Symbolic significance

Disgruntled Sunni leaders complain that national resources are being channelled to the Shia militias instead of the state forces.Well-placed sources cite one instance where they say a consignment of 67 armoured Humvees sent for the army by the United Arab Emirates were diverted to the militias, with the defence minister not even knowing about it. They say donations from the UAE abruptly stopped.

Optimists will be hoping that the talks in Baghdad involving the Iranian defence minister, and Mr Abadi's earlier discussions on Sunday with the head of US Central Command, Gen Lloyd Austin, will have produced commitments that could mitigate the sectarian impact of the Shia intervention.

The Americans made light of the fall of Ramadi, dismissing it - as Bashar al-Assad did with his recent losses in Syria - as part of the ups and downs of a long-running war.

But, like the struggle for Kobane in northern Syria, the battle for Ramadi had a political and symbolic significance greater than its considerable strategic value.

The Pentagon said it would "just have to help the Iraqi forces get it back later".

It will now have to decide whether it will use its air strikes - which it had stepped up in support of the Iraqi army at Ramadi to no avail - to back the Shia militias deep inside the Sunni heartland, inevitably helping the spread of Iranian influence and control.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home