Court Ruling Could Hinder U.S. Investigation of Islamists

By Johanna Markind

The political struggle over the right balance between protecting the public and avoiding undue intrusion into private lives has taken a detour through the courts. Last month, a federal appeals court reinstated a complaint against the New York City Police Department in a decision with repercussions for the federal government's domestic intelligence apparatus. If the court's decision stands, it may make it harder for the government to prevent trouble by looking for extremists who act under a religious ideology, like Islamists.

During the 1990s, when journalist Steve Emerson began investigating Islamist groups in the United States – whose leaders exhorted their members to wage jihad to "destroy the West" and "kill the Jews" – he contacted FBI officials and asked whether they knew what was going on. He was astonished to discover that they didn't. Even if they had known, they told him, there was little they could do about it "owing to the FBI's mandate to surveil criminal activity and not simply hateful rhetoric," as Emerson writes in his book American Jihad.

The ability of federal agencies to gather domestic intelligence was sharply curtailed in the 1970s.

|

After 9/11, the limits on domestic surveillance were relaxed. The federal government once again authorized the FBI and other federal agencies, like the NSA, to gather information about US citizens and foreign nationals within the United States.

After 9/11, the limits on domestic surveillance were relaxed.

|

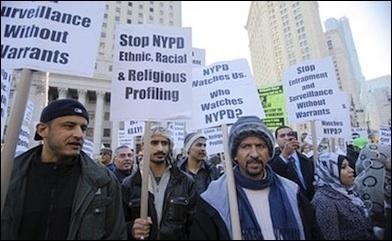

In 2012, a group of Muslim individuals and organizations filed suit in New Jersey federal court alleging that the City of New York violated their rights under the Equal Protection, Free Exercise of Religion, and Establishment Clauses by the NYPD's investigative activities, some of which (allegedly) occurred in New Jersey. The plaintiffs did not claim that the police tapped their phones, read their mail, or did anything other than obtain publicly available information. Nevertheless, title plaintiff Syed Hassan and the others claimed that police used their Muslim religious identity as a "permissible proxy for criminality" and caused them harm by stigmatizing them. The court dismissed the lawsuit on February 20, 2014.

The plaintiffs claim that police used their Muslim religious identity as a "permissible proxy for criminality."

|

The plaintiffs appealed the dismissal. On October 13, 2015, the US Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit reversed the lower court's decision and reinstated the claim. The appellate court held that the lower court was wrong to conclude the plaintiffs lacked standing to sue. Under the Third Circuit's analysis, the plaintiffs had suffered an injury from the alleged police activities, and the injury would likely be redressed – in other words, the problem would be fixed – if they won the suit.

In reaching this result, the Third Circuit held that subjecting individuals to government surveillance based solely on their religion, as plaintiffs claimed, was enough to state an injury. (At this stage, the question isn't whether the plaintiffs have proven their claims, just whether their claims are enough to get them into court.)

The Third Circuit also concluded that the lower court should have held the government to a higher standard in deciding whether its actions were proper. The lower court had applied a rational basis test, meaning the government's actions would pass muster under a showing that they were rationally related to a legitimate governmental objective. As the appeals court noted, courts generally place the burden on the challenger to show that the government's actions are not rationally related to a legitimate goal. Plaintiffs' claim of religious discrimination was entitled to a less deferential standard, the higher court held.

The majority decision failed to clarify what standard the lower court should apply.

|

The court's decision means that the case will be sent back to the trial court and plaintiffs will have the opportunity to prove their claims in court – unless the decision is appealed and the Supreme Court agrees to hear the case or unless the full panel of all Third Circuit judges decides to rehear the case; the recent decision was made by the normal three-judge panel.

For those keeping a scorecard, here are some things to watch:

- Will the City of New York seek a rehearing from the full Third Circuit panel? If not, will it appeal to the Supreme Court and, if it does, will the high court accept the case? If an appeal is filed, it will also be worth noting whether the United States Department of Justice weighs in. President Obama isn't exactly reputed to have the back of either police or the national security apparatus. But maybe for just that reason, he'll feel compelled at least to act as if he wants to support them.

- If and when the case returns to the trial court, it's a safe bet that the court/jury will uphold the governmental objective of preventing another terrorist attack as satisfying any standard. The tougher questions will be whether the plaintiffs can show they were targeted purely because of their religion, and if so, whether the police actions were sufficiently tailored. The case could very well be decided by the court's decision of which standard to apply.

- Will the Third Circuit's holding, that being singled out for intelligence-gathering constitutes an injury (at least, if the singling out is based on a religious classification), hold up? If so, what repercussions will this have for domestic intelligence gathering? In essence, will police, the FBI, the NSA, etc., have to satisfy something like a warrant standard just to open an investigation – even information that may be collected without a search requiring a warrant?

The court has made it harder for government to track violent movements that use religion as their organizing principle.

|

Part of the problem here is that political leaders (see, e.g., here, here, here, here, here, and here) and outspoken, supposedly representative Muslim groups like the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) (e.g., here, here, here, and here) have repeatedly denied any link between Islam and the violence and totalitarian nature of groups like al Qaeda and ISIS and their followers. More specifically, they have actively worked to obscure the relationship between Islam and Islamism – and therefore, have obscured how the two are different. Investigators charged with public safety have been left to figure this out for themselves, and now are being rewarded for their efforts by being exposed to a lawsuit.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home